Wednesday, Dec 18, 2019 10:00 [IST]

Last Update: Wednesday, Dec 18, 2019 10:00 [IST]

“Wilt thou the bloom of springtide, the fruit of the year that doth wither?

Wilt thou what charms and pleases? Wilt thou what fills and keeps fed?

Wilt the earth and the heaven in one name mingle together?

I name, Sakuntala, thee, and so is everything said.”

(Goethe)

Kalidas wrote only three dramas, amongst which “Abhigyana Shakuntalam” is a love drama based on the well-known story of Dushyant and Shakuntala, as is told in the Adiparva of Mahabharata (chapters 67-74), but deviated in many places as suited his imagination as a poet. The plot of the story is quite succinct:

Dushyanta, king of Prathisthan, in course of his hunting expedition, accidentally reaches the hermitage of Kanva, who was at that time on some errand leaving his adopted daughter Shakuntala alone. Smitten with love at the first sight, the king asked her hand in marriage when he learnt that she was a king’s daughter. When the king promised to appoint her son his successor, she gave consent and marriage was performed in Gandharva form. Being apprehensive of the sage’s anger, the king very soon leaves the hermitage. Divining what has transpired on his return in his absence, the sage gratulates Shakuntala on her choice. Still being apprehensive of sage’s anger, the king dares not send for Shakuntala. She was enceinte and after three years gives birth to a son. Even at the age of six, the child was extremely turbulent, therefore, named “Sarva-damana” (A person who could subdue anybody). The sage then decides to send him to his father’s place to be installed as heir-apparent. Shakuntala along with her son and some disciples go to the king’s palace. The king remembers everything, but being fearful of public’s calumny, denies having his any relation with her. At this moment, an aerial voice intervenes and supports Shakuntala’s statement, and directs the king to accept her as his legal wife. Finding no excuse, the king welcomes her as his chief queen and her son as his heir-apparent.

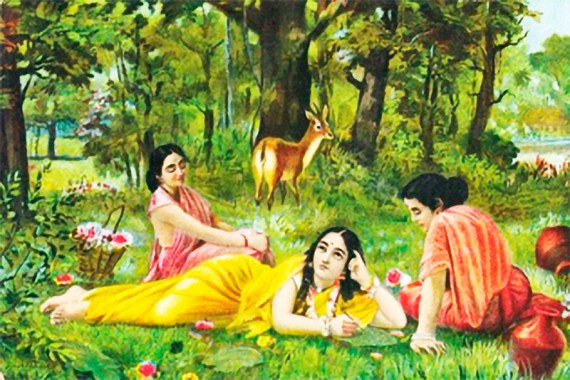

This is a very simple, drab and boring story without any speck of romance. Like Shakespeare, who rarely followed the original plot in his plays, Kalidas too handled this prosaic story of the Mahabharata in such an innovative and ingenious way that the dry skeletons converted into flesh and blood and vitality and alive and became immortalised forever. His foresightedness knows no bound in the story. In the original story, the king goes to the hermitage accompanied by his retinues, but being doubtful of hamper in further progress in the plot, the playwright deviates and presents the king going alone into the hermitage in tiredness after daylong pursuance of the deer. The poet in order to prolong the conversation between the king and Shakuntala creates two innocent characters Anusuya and Priyamvada to mediate. The girl’s love for the king and her bashfulness has been fragrantly depicted. In the meantime, Shakuntala is attacked by a bee, which brings her more close to the king, which in fact is a unique creation of Kalidasa’s imagination.

In the original story, the sage is out of the hermitage only for a few minutes , but the poet considering this space of time too small to woo a girl, makes the sage Kanva absent for a few months on a pilgrimage. In order to break the dull monotony of the love talks and allow the king to progress in his amorous affair with Shakuntala, the poet creates a jester-confident of the king, Vidusaka, though his role is limited. In the third act, the poet has dispensed with the selfish bargain of Shakuntala to make her son heir-apparent in the event of solemnising marriage with the king. Rather he projects the love malady of Shkuntala, her innate bashfulness, her conflicting emotions in her heart, and finally her modesty.

Though the original story relates that Shakuntala is retained in the hermitage for nine years, Kalidasa finds this behaviour of Kanva unbecoming of a father, and therefore deviates from the original plot and makes the sage to send his daughter on the very day he becomes aware of her marriage and before her son is born. In the original story, the king feigns ignorance, but the poet in order to absolve the king from moral responsibility ingeniously creates the episode of the sage Durbasa’s imprecation clouding the king’s memory. This is really Kalidasa’s greatest innovative faculty. “That there may be an ultimate recovery of memory; the curse is so modified as to last only until the king shall see again the ring which he has given to his bride. To the Hindu, the curse and modifications are matters of frequent occurrence; and Kalidasa has so delicately managed the matter as not to shock even a modern and western reader with a feeling of strong improbability. Even to us, it seems a natural part of the divine cloud that envelops the drama, in no way obscuring human passion, but rather giving to human passion an unwonted largeness and universality.” (A.W.Ryder) This episode evolves an earthly love into divine love. Bhavabhuti in his masterpiece Uttara-Ramacharitra while depicting Sita’s banishment and pathetic wailing of Rama closely follows this particular portion of the story of Shakuntala.

Observing some similarity in the story of Shakuntala with that of described in the Padma-Purana, Swarga-khanda, some scholars dare to comment that Kalidasa drew all his materials from the Padma-Purana. But the Padma-Purana in its present form is of recent origin. Even if we accept that the kernel of Padma is very old, the story of Shakuntala is definitely a later interpolation, its language and idioms clearly depict this fact. This apart, the author of the Padma-Purana, while narrating the story of Rama follows not the Ramayana of Valmiki, but takes the outlines of the story from the Raghu-vamsam of Kalidasa. Therefore, the author of the Padma-Purana was either a later author or an interpolator.

The Abhigyan-Shakuntalam of Kalidasa is a supreme oriental romance: colourful, gorgeous and delicate. The whole story revolves around a heroine Shakuntala, who is delicate, coy, beautiful, and charming, but at the same time sweet par excellence and firm in her resolve. She is an untouched beauty and a full-bloom rose in all its freshness. She is not Miranda of Shakespeare, a simple maiden who grew up in the company of one enslaved nature-spirit called Ariel. Shakuntala is an embodiment of love, who manifests in herself a dignified bliss of love spiritual. She is out and out an earthly creature evolved to maturity in raptures and pangs surrendering herself to her senses. But she was beyond all these, because her birth, life and training pushed her to spirituality. True, love without spiritual base simply proves sensual and transitory in course of time. Prima facie her life looks like the vastness of an arid desert, where there is nothing but void, which has been subjected to treachery, intense agony and gloom, however, which also unmasks before her the futility of earthly love. But from this entire antithesis emerge a purified soul, who is an abode of bliss and dignified in appearance like a goddess. Her whole life is a systematic journey from fleshy pleasures to spirituality, from dejection to austerity. True love is revealed only when desires are conquered. When Shakuntala surpasses all her earthly desires, there comes Heaven to her rescue, and her lover realizes his fault. It was only Kalidasa’s fertile imagination which could create such a setting. The entire story of Shakuntala is a projection of soul’s journey from finiteness to infinity, from ephemeral earthly love to everlasting blissful love. She is a supreme example of sacrifice but without any complaint or grudge against anybody. Shakuntala, in short, epitomises the basic characteristics an Indian womanhood.

“Wouldst thou the young year’s blossoms and the fruits of its decline,

And all by which the soul is charmed, enraptured, feasted, fed?

Wouldst thou the earth and heaven itself in one sole name combine?

I name thee, O Shakuntala and all at once is said.”

(Woolfang Von Goethe)